The Illusions of Neurocritical Care

Our ability to make sense of the world is highly dictated by the context in which we make observations. The problem is that our observations are often illusions.

A journal article published last summer (Meyfroidt et. al., 2022) provided an update on TBI management and stated that “ICP management” has been confused to mean “TBI management.” The paper makes the case that managing TBI solely with ICP is like the blind man trying to describe the elephant by only feeling its trunk. Monitoring ICP is valuable when it signals an expanding brain, but it is detrimental when a “normal” ICP promotes complacency in management. Current recommendations set the “normal” threshold of ICP at 22 mmHg—a number that was obtained from a single paper published out of Cambridge by our friend Peter Smielewski.

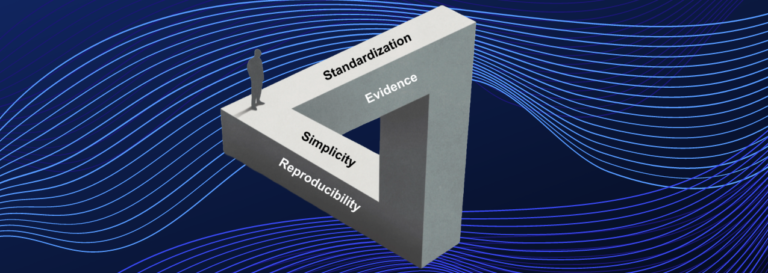

ICP became a standard (in my opinion) mostly because it was one of the few brain modalities that could be monitored continuously back in the late 1970’s and not necessarily because it was the best metric for TBI management. Even four decades later there is no level 1 evidence for an ICP treatment threshold. Yet, it is a standard of care, creating the Illusion of Evidence.

My eyes were opened to this management confusion early in my career as an entrepreneur. In the early 1980’s we had just commercialized the first numerical descriptor of EEG activity, the Spectral Edge Frequency (SEF), in a product called the Neurotrac. Early papers showed it could track anesthetic depth as well as identify periods of cerebral ischemia.

After it had been on the market a few years, I got a letter from an anesthesiologist at Columbia in New York saying the SEF was fine throughout a carotid endarterectomy surgery, but the patient woke with a hemiparesis and a demonstrable stroke. We quickly added warnings to the use of the metric to include viewing the raw EEG to verify a change. It was self-evident that you could not assess brain function with just one number. Despite this, the Illusion of Simplicity in neuromonitoring and neurocritical care continues to prevail.

More recently, descriptors are emerging into mainstream neurocritical care including an autoregulatory index PRx and the optimal cerebral perfusion pressure, CPPopt. Numerous publications and a recent trial show their value in patient management. However, we have seen, including in our own work, differences between implementations of the algorithms from their published descriptions and the gold standard ICM+ software–the reproducibility of complex algorithms with many hyperparameters is exceptionally difficult by virtue. We expect this Illusion of Reproducibility to become even worse unless algorithms become consistently documented.

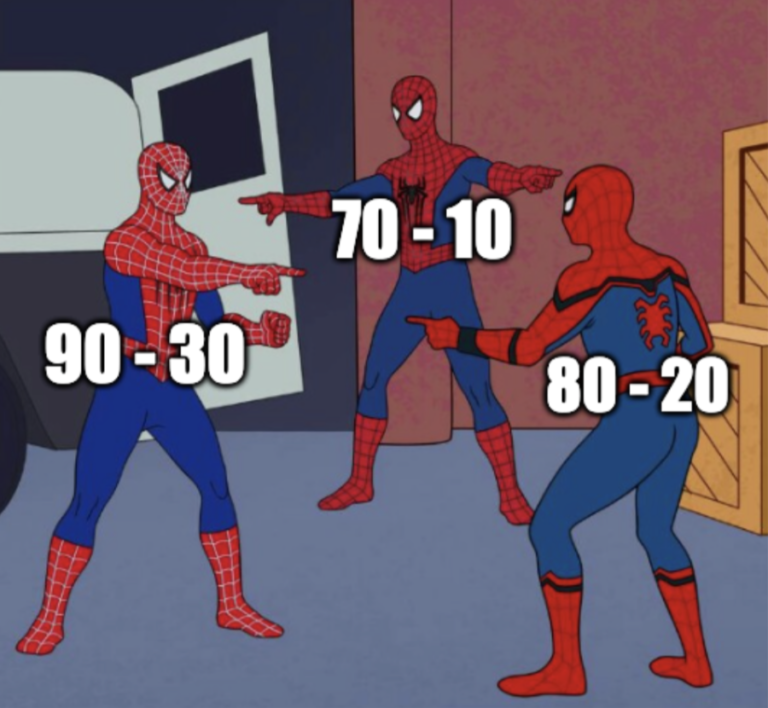

Optimizing CPP is only useful if we can reliably measure it. I’ve written part of this editorial while listening to a talk on CPP by our friend Dr. Sergio Brasil at the Euro Neuro conference in Brussels. Though guidelines recommend a CPP of 60, he showed that a CPP of 60 with a blood pressure of 70 and ICP of 10 (70-10) is different from a CPP of 60 with a blood pressure of 90 and ICP of 30 (90-30) (Brasil et al., 2023).

Further complications arise with inconsistencies in how pressure waveforms are both measured and interpreted. To help characterize this variability, Dr. Sergio Brasil is conducting an international Delphi process on the topic of intracranial pressure waveform morphology. You can contribute here. Opportunities like these help in minimizing the Illusion of Standardization by collecting knowledge from people in the field to shed light on how heterogeneous the treatment of brain injury actually is.

These illusions are barriers to innovation; they confuse our expectations of how things actually are and stand in the way of new technology. How do we make progress? To be fair, neurocritical care is a new specialty and our understanding of brain injury is in its infancy. In a sense, we are still figuring out “what” we want to describe as we are figuring out “how” to describe it. But we need to make sure we don’t create ruts we can’t get out of just because a method is easy, available, or affordable.

History tells us not to rely on numerical descriptors of brain function unless you understand their assumptions and limitations. Viewing a multimodal display of the raw data should always be the base from which you move to a summary descriptor. Much work is needed to extract this guidance from all of this information. Only then will the illusions fade, and we will be able to see reality within the field of neurocritical care.